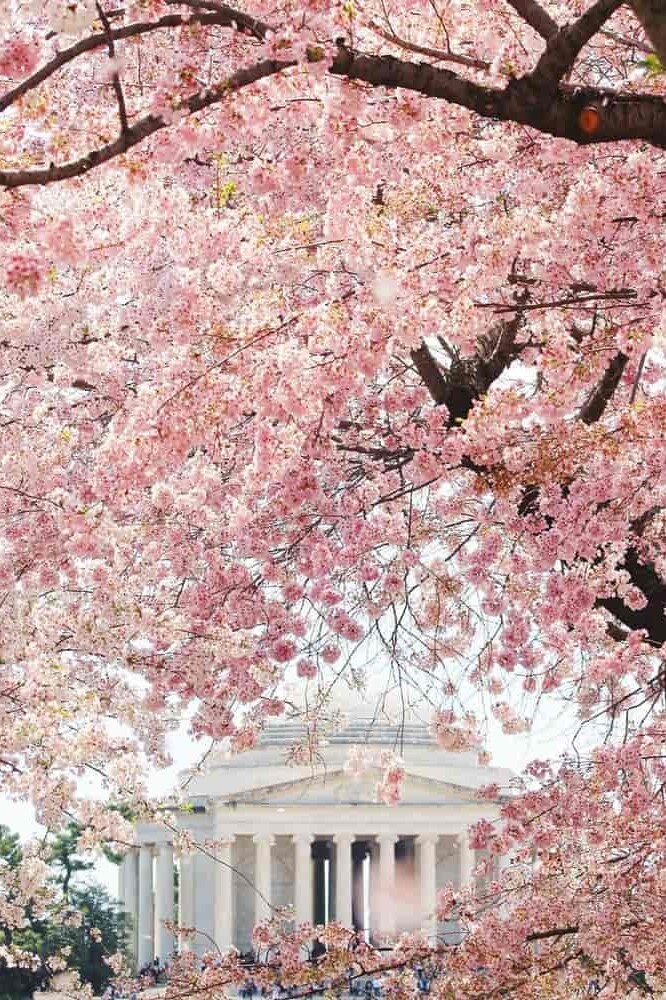

They went on the train. Four of them: a father and mother, a boy and a girl. The train was called the Senator. It went from Back Bay Station to Washington, DC. The president lived there, in the White House. There were monuments, a museum with a space ship, and cherry blossoms that would bloom when they got there.

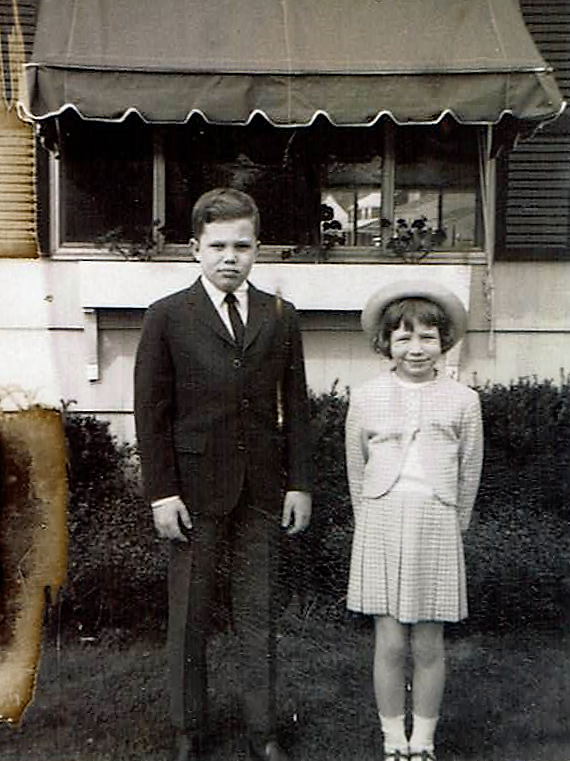

It was an important trip. Aunt Louise had given them her old luggage, navy blue suitcases that matched. The father had a new umbrella, the mother a new spring coat. The boy wore a navy jacket and a white buttoned shirt with a necktie like a grown-up. The girl had a new suit, the Washington Suit. It was lavender and white checks with a pleated skirt and a jacket with a round neck. A saucer hat and white gloves because it was an important trip.

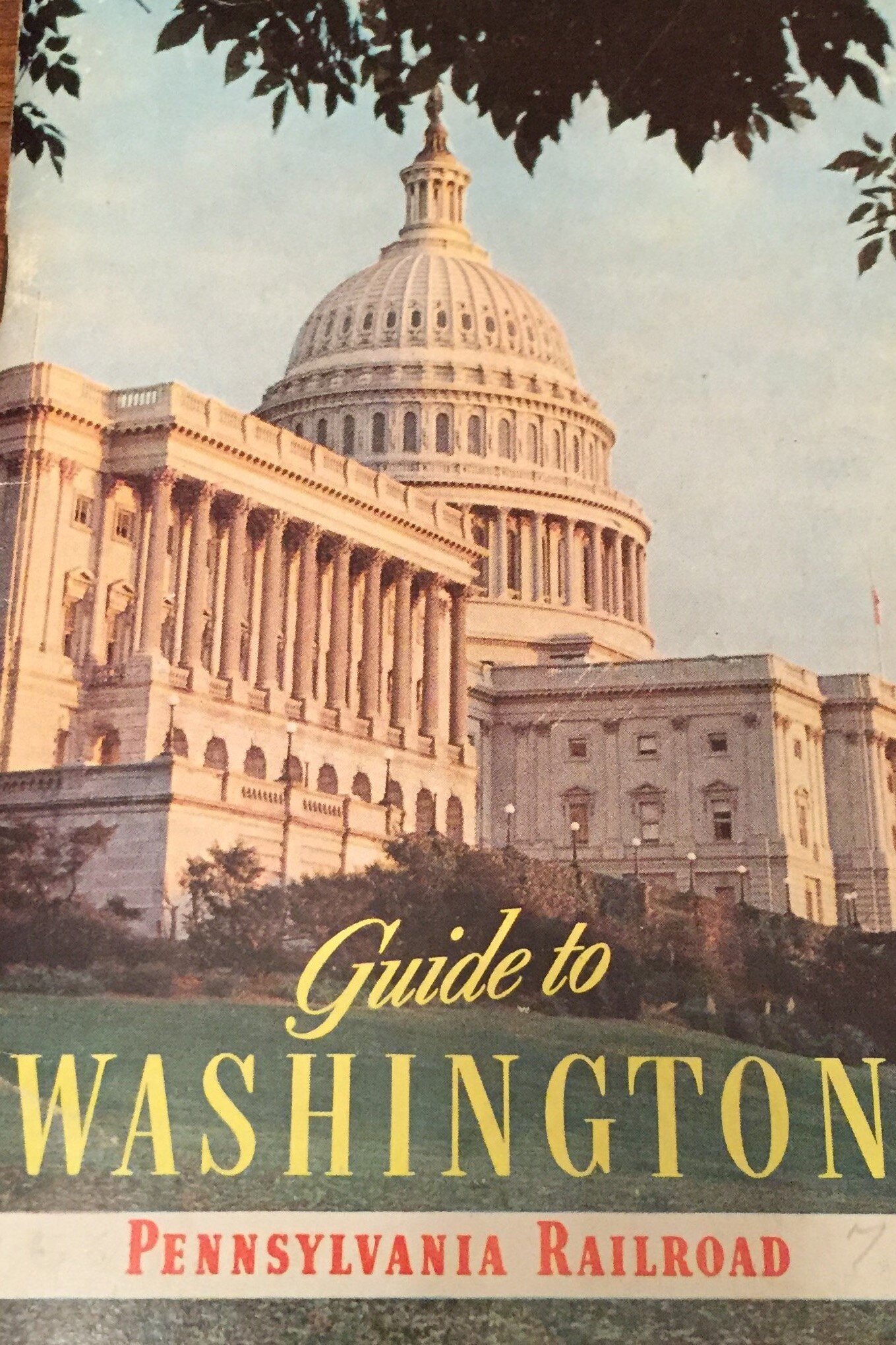

The father hadn’t been to Washington since he was a soldier in the war. He said that back then so many people were going to Washington you couldn’t get a seat on the train, but had to travel standing up. Now they had a reservation. Coach it was called. You sat in an upholstered seat looking at the back of the seat in front of you. It had a sign that said, ‘Thanks for riding Pennsy.’ The railroad was called the Pennsylvania, though it went to a lot of other states too.

On the train you could look out the window, read a book, or pull down the little table in the back of the seat in front of you and draw. The ride would take all day. The train stopped in cities along the way, like New London, New Haven, and New York. Then the cities weren’t News, but had one-word names like Philadelphia and Baltimore.

At lunchtime the family left their seats and went to the dining car. The father and the brother, the girl with her mother. This was definitely something to have a grown-up along for because the door at the end of the car was heavy. You had to pull it hard and cross into the between-cars section, which was dark and very loud with the sound of the rushing train. It shook. If you looked down you could see daylight through the places where the cars were stuck together. There was a worrisome minute when it seemed possible that the cars might come apart or that your mother might not be strong enough to pull open the door to the next car, and there you would be between-cars when they might come apart. But that never happened. Instead you entered the Dining Car.

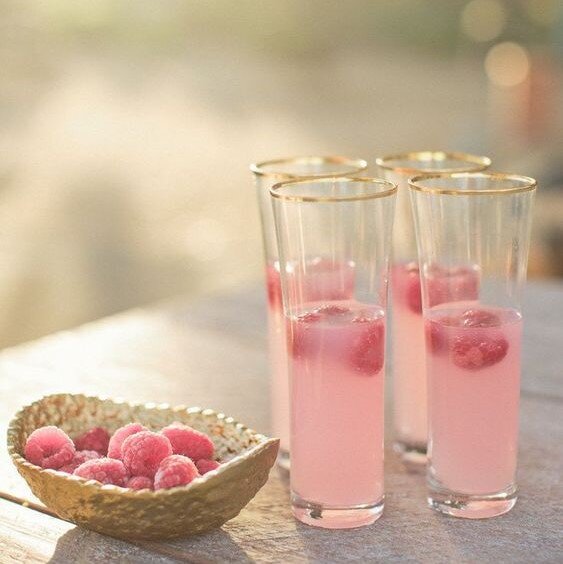

The Dining Car wasn’t like Coach. There were tables along each side, under the windows. They were covered in white tablecloths and set with china and glasses and silverware. Passengers sat at the tables eating and talking in low voices. The scenery rushed by while they ate. It was quiet and elegant. The train chugged along and sometimes the water sloshed a little in the glasses, but it never spilled. The mother explained that the waiters knew exactly how high to fill the glasses to keep them from spilling over. On a ship they might need to wet the tablecloth to keep the dishes from sliding off, but on the train it didn’t jostle as much.

A tall, dark-skinned man in a white jacket showed them to their table. He handed out the menus. To the girl’s surprise, he left a card and a pencil at her place. The mother and father explained that on the train one passenger writes the orders on the card for everyone at the table. The Pennsylvania Railroad supplied a pencil; the girl noted that it didn’t have an eraser. Well, she was far into first grade. She’d worked hard on penmanship. The waiter, who knew exactly how high to fill the water glasses, seemed to think she was the one to write the order. She’d have to give it a try.

It was a good thing there were a lot of lines on the card because each order had a lot of words. But with careful work the card was ready. The waiter returned. He picked up the card and studied it. Maybe the penmanship wasn’t good enough for the Pennsylvania Railroad. No, he nodded crisply and placed the card in the pocket of his jacket. Businesslike. Just like all the other tables in the Dining Car where one passenger writes the orders on the card for everyone at the table.